|

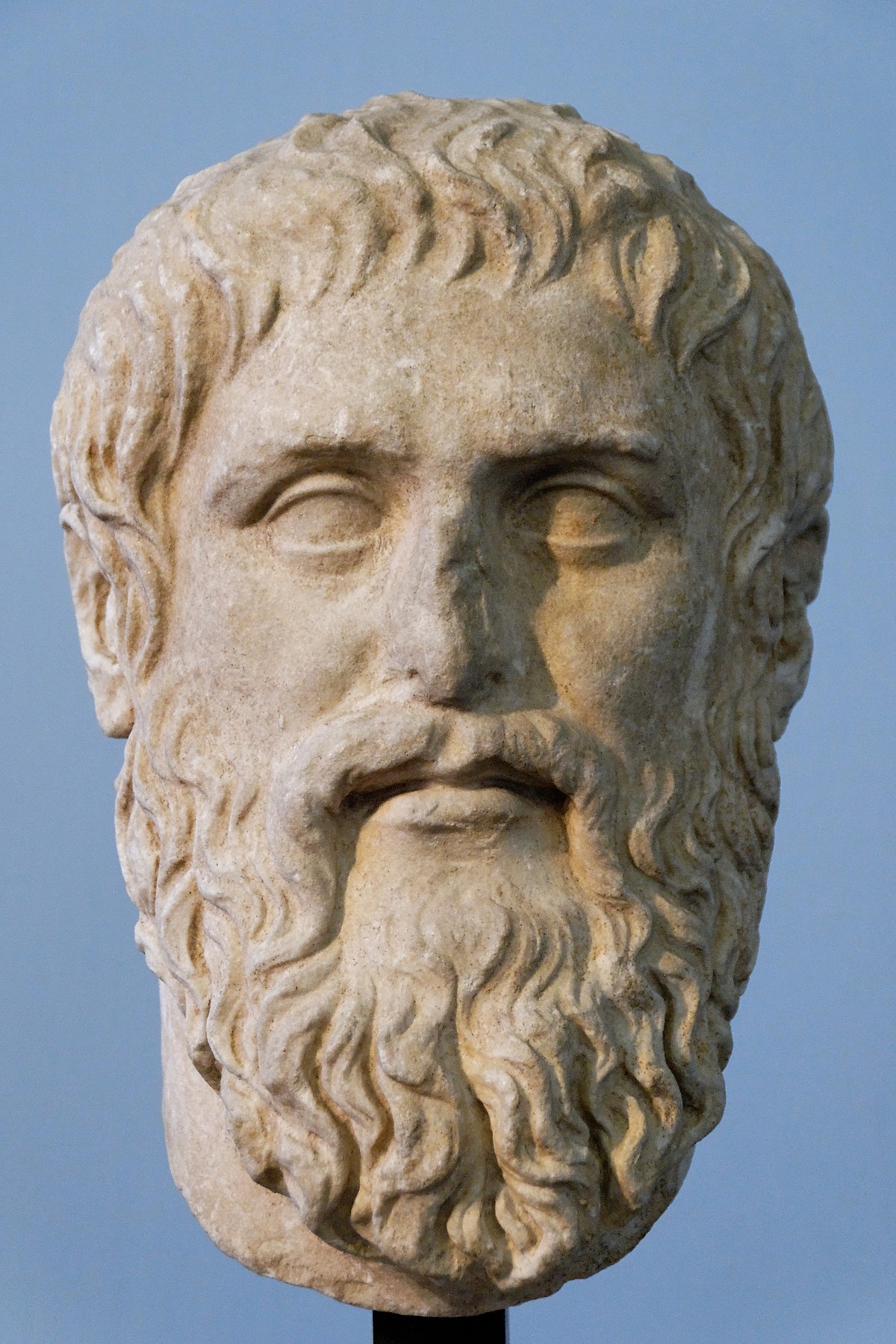

| What can Plato tell us about today? (Commons) |

Enter Plato, who attempted to define what exactly makes up true knowledge, or he sometimes put it, 'justified true belief'. Without delving into too much technicalities (I'm only a generalist/medical student after all), Plato detailed in one of his well known works Republic the analogy or theory of the divided line. In it he imagines a line that can be divided into two parts; the upper part represents knowledge or absolutes grounded in such things as mathematical reasoning and philosophical understanding (these actually represent subdivisions of the upper line and are a matter of some controversy but in short the upper line is generally as such).

The lower line represents the visible, perceived world. It constitutes belief and opinion based on mere perception. To understand this, consider the blue sky above. You could imagine that the sky is indeed a solid dome of blue sapphire (maybe even seven heavens for that matter) that encloses our space and prevents demons from entering our realm of existence. But we all know that's not true but how?

Plato also detailed similar ideas in the allegory of the cave which you can watch in the following short video:

These undesirable conclusions open up a Pandora's box of troubles. The enormity of this year's Ebola outbreak may have something to do with such sentiments on an individual as well as a regional level. The perpetual conflict in the Middle east and North Africa may be because we are looking at the shadows and not looking for the old men to lead us to the answers. We (the international community) think we know the truth because we focus on the shadows (the mass media reports and the social media reports). Given the advances in media technology, this is dangerous because the prisoners can shout down the enlightened more effectively, a capability well exploited by the ISIS group in Iraq.

So here's what could happen; we could all get wiped out by Ebola, whole civilisations can get destroyed (cue the mass exodus in Iraq) and there could be a slow slide into stagnation. I would like to revisit this last possibility in a future post.

How can we save the knowledge society? I sincerely don't know but I guess it will involve a lot of perseverance and backing up of books, files and other materials.